LISTEN. Leibniz searched harder for fame and philosophical reputation, I suspect. But he did invent the calculus. Or

maybe he and Newton both did, in a nice

pre-established harmony of genius invention. There's no denying Leibniz's intelligence, but there is some question as to his grasp of the depths of human suffering.

A monad, says the

Philosophical Dictionary, is "a complete individual

substance in the philosophies of

Conway and

Leibniz, who supposed that

each contains all of its properties—past, present, and future."

"Leibniz maintained,"

writes Anthony Gottlieb, "that the “true atoms of nature” follow patterns that are implanted in advance by God: “everything happens to each substance as a consequence of the first state God gave to it.” The same is true of people, according to Leibniz--everything that they will ever think or do is fixed before they are even born--but this does not mean that they cannot exercise free will..." It doesn't? Then

free will doesn't mean what most of us think it means, namely the capacity to think or do something that wasn't already fixed.

Anne Conway came up with the term "monad" and lent it to Georg W.F. Leibniz, who bent it to mean something very different from her more Spinozistic view that "all beings are modes of god, the one and only spiritual

substance." His monadology, coupled with

theodicy ("an attempt to explain or defend the perfect benevolence of god despite the apparent presence of

evil in the world"), resulted in one of the more bizarre and bloodless metaphysical systems ever devised by the mind of man... or monad. Matthew Stewart tells the tale of Leibniz's attempt to one-up the humble lens-grinding pantheist Spinoza in

The Courtier and the Heretic. "The difference between Leibniz and Spinoza on happiness, as on all subjects, comes down to their different attitudes toward God..."

And towards material reality, and humane credulity.

Leibniz rejected the Cartesian account of matter, according to which matter, the essence of which is extension, could be considered a substance. Leibniz held instead that only beings endowed with true unity and capable of action can count as substances. The ultimate expression of Leibniz's view comes in his celebrated theory of monads, in which the only beings that will count as genuine substances and hence be considered real are mind-like simple substances endowed with perception and appetite... this position, denying the reality of bodies and asserting that monads are the grounds of all corporeal phenomena, as well as its metaphysical corollaries has shocked many. Bertrand Russell, for example, famously remarked in the Preface to his book on Leibniz that he felt that “the Monadology was a kind of fantastic fairy tale, coherent perhaps, but wholly arbitrary.” And, in perhaps the wittiest and most biting rhetorical question asked of Leibniz, Voltaire gibes, “Can you really believe that a drop of urine is an infinity of monads, and that each of these has ideas, however obscure, of the universe as a whole?” SEP

No, not really. My hunch is that Leibniz was motivated more by a hunger for attention, notoriety, and philosophical distinction, a desire to distinguish himself from the pack of rationalists like Spinoza and Descartes. [

Leibniz vs. Spinoza] My judgment aligns with

William James's, that

Leibniz's philosophy is superficial, feeble, cold, and unreal. But it's entertaining, and it's a useful prod to hold our philosophers to a standard more humane and relevant to the actual experience of real human beings. Voltaire's

Candide, “stunned, stupefied, despairing, bleeding, trembling," asked the right question: If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the others like?” I don't want to know. If this is

scientific optimism, I'll pass.

I'll pass on pessimism too. James's pragmatic meliorism is the sane alternative, in a world of woe (and joy, and all points in between) like ours.

...there are unhappy men who think the salvation of the world impossible. Theirs is the doctrine known as pessimism. Optimism in turn would be the doctrine that thinks the world's salvation inevitable. Midway between the two there stands what may be called the doctrine of meliorism... Meliorism treats salvation as neither inevitable nor impossible. It treats it as a possibility, which becomes more and more of a probability the more numerous the actual conditions of salvation become. It is clear that pragmatism must incline towards meliorism... Pragmatism: A New Name for an Old Way of Thinking... Refillism

And it's clear that a world in which a

Holocaust can happen must work harder for its salvation than the refined monistic theodicy of a Leibniz could ever manage to do.

Two Holocaust survivors are visiting our campus this afternoon. The number of living witnesses to this historical human abomination and rebuke to over-refined rationalist-

intellectualist philosophies is dwindling fast, we must hear their stories and learn their lessons while we still can.

Soon there will be no more. Holocaust

memory must conquer irrational, immoral

denial.

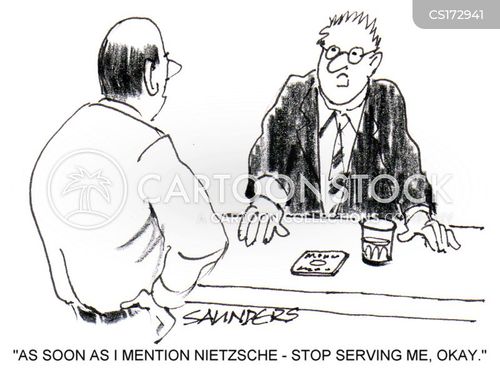

Fortunately we'll still have the written testimony of literary and psychological heroes like Viktor Frankl, whose

Man's Search for Meaning is an amazing, inspiring document that attests to the power of endurance. He quotes Nietzsche: “Those who have a 'why' to live, can bear with almost any 'how'.”

We had an excellent

report on Existentialism Monday in CoPhi, out on the JUB stoa. Its gist was also Frankl's message: “Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather must recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible.”

Leibniz really had no clue.

Spinoza Quotes

Spinoza Quotes