But you don't need to follow anybody. https://t.co/5IJqYxBL8x pic.twitter.com/WCcUQxToX5

— Phil Oliver (@OSOPHER) December 8, 2021

And look for me on Bluesky @osopher.bsky.social & @wjsociety.bsky.social... president@wjsociety.org... Substack https://philoliver.substack.com (Up@dawn@Substack)... and Mastodon @osopher@c.im... (Done with X and Meta)... Continuing reflections caught at daybreak, in a WJ-at-Chocorua ("doors opening outward") state of mind...

Sunday, December 12, 2021

Philosophy Twitter

Wednesday, December 1, 2021

Kosmic cheer

Tuesday, November 30, 2021

Happiness is

LISTEN. Happiness meets for the last time in 2021 today, scheduled to return in '23.

I've taught this course biennially for quite a long time now, and I still don't think we can do better for a coda than Charles Schulz. Happiness is a warm puppy. And really, it's "anyone and anything at all/That’s loved by you."

So our parting takeaway has to be: love profligately, and love well.

And don't be Sally Brown.

Monday, November 29, 2021

Last words

LISTEN. Back from Thanksgiving, it's time to wrap things up and send the classes of Fall 2021 out to meet their uncertain futures. The usual last words apply, there really are no fortunes to be told. There definitely is advice to be given, however. Do stay curious, kids, do keep asking questions. And do keep in touch.

It was nice to hear again from my old grad school friend the Biochemist, who makes a point of sending out holiday missives every Thanksgiving and Valentines Day that keep our old far-flung and socially distant 80s cohort in touch in spite of ourselves.

She confessed some despondency in this Thanksgiving letter, "over the state of the country ... and yet I want to be optimistic. But I am genuinely scared about all of the unraveling I see around me."

Many of us feel that way, on occasion. Several of us agree that the daily news cycle is indeed frightful. We're learning to monitor and regulate our exposure to the worst of it. Better to start the day with a little history and poetry.

And best to heed old Henry's sunny words at the end of Walden. A morning atmosphere, at any time of day, is tonic. Wake up. Get up. Do something. Don't stare too long or hard at the light that would put out your eyes. Dream of dawns to come. Build your castles in the air and start climbing.

Listen to Mark and Maria:

"When you arise in the morning, think of what a precious privilege it is to be alive - to breathe, to think, to enjoy, to love… Dwell on the beauty of life. Watch the stars, and see yourself running with them." --Marcus Aurelius“Mingle the starlight with your lives and you won’t be fretted by trifles.” --Maria Mitchell

And listen to the Almanac's trademarked wisdom. Be well, do good work. and keep in touch.

Oh, and to my old epistemologist friends who responded to that holiday letter with worries about "the problem of criterion," "infinite regresses of reasons," whether children or anyone else have justified beliefs, and various "meta-issues" in philosophy etc. I say: When you erkenntnistheorists finally settle those meta-issues, I hope you'll tackle the bigger one. We're all already justified in believing the metaverse is going to be big trouble.

Tuesday, November 23, 2021

Eagerness

The problem I have set myself is a hard one: first, to defend (against all the prejudices of my "class") "experience" against "philosophy" as being the real backbone of the world s religious life I mean prayer, guidance, and all that sort of thing immedi ately and privately felt, as against high and noble general views of our destiny and the world s meaning; and second, to make the hearer or reader believe, what I myself invincibly do believe, that, although all the special manifestations of religion may have been absurd (I mean its creeds and theo ries), yet the life of it as a whole is mankind s most important function. A task well-nigh impossible, I fear, and in which I shall fail; but to attempt it is my religious act. Letters, April 1900

He wants us to feel that dependency, and to respond with appropriately energetic responses. If we couldn't feel we'd be lost. We'd like nothing, dislike nothing, value nothing. Life would be insipid, and insignificant.

Wherever a process of life communicates an eagerness to him who lives it, there the life becomes genuinely significant. Sometimes the eagerness is more knit up with the motor activities, sometimes with the perceptions, sometimes with the imagination, sometimes with reflective thought. But, wherever it is found, there is the zest, the tingle, the excitement of reality; and there is 'importance' in the only real and positive sense in which importance ever anywhere can be.Zest, tingle, excitement, joy: by any other name, that's the prize that makes life worth living. Emerson crossing his common, Wordsworth tramping his mountains and lakes, Whitman on the ferry and omnibus all had it. They defied their "highly educated" class status for it.

B.P. Blood may not have had it, but he had a mystics's sense of ineffable reality. James thought he also had a pluralist's sense of variable reality. He somehow had James's ear, in any case, and gave him his "last word... “There is no conclusion. What has concluded, that we might conclude in regard to it? There are no fortunes to be told, and there is no advice to be given.–Farewell!” *

The solid meaning of life is always the same eternal thing,— the marriage, namely, of some unhabitual ideal, however special, with some fidelity, courage, and endurance; with some man 2 s or woman 's pains.—And, whatever or wherever life may be, there will always be the chance for that marriage to take place.

==

Monday, November 22, 2021

Elevated

LISTEN. It's the short week before Thanksgiving break, and just a couple class days remain of the Fall semester after it. It's getting late real early, as Yogi said. (He really didn't say everything he said.)

So we'll step it up in CoPhi today, looking at James on habit and consciousness. We'll preview some of our final reports as well, and get started reviewing for our last exam. Busy time. We should be grateful. That's our story, everybody's story. Happy Thanksgiving!

We saw Tick Tick Boom last night, Lin-Manuel Miranda's paean to his hero Jonathan Larson, to creative perseverance, and to friendship. I give it all the stars.

Oh, and by the way... on Saturday I finally went and did that skin-deep, self-indulgent thing I almost did last May, before surgery forced a postponement. I know it's no big deal to my students' generation, but to mine it still feels subversive and transgressive and a little risky. "Bad ass" even, said Younger Daughter. Stats and anecdotes are mixed on the matter of regret.

But I can't imagine ever regretting an arms-length reminder to regard the recurrent daily light of dawn as a perpetual invitation to wakefulness and, well, to creative perseverance. Morning is "when I am awake and there is a dawn in me," when (like Henry) I'm most susceptible of enlightenment.

I do not say that John or Jonathan will realize all this; but such is the character of that morrow which mere lapse of time can never make to dawn. The light which puts out our eyes is darkness to us. Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star.

And John Kaag's students "just shrug and say, 'Yeah, whatever, the guy is woke.'"

Yes, he was. I want not to forget to set my internal alarm too. The arm's just a post-it. We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn, which does not forsake us in our soundest sleep. I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor.

Elevate, and maybe even transcend.

LISTEN (11.11.21). Today in Happiness CoPhi our focus is Habit, a chapter in James's Principles of Psychology and an anchor of the happy life.

James wrote Principles better to understand the origin of consciousness, but habit's great gift is its harnessing of the power of unconscious autonomous activity, thus freeing the conscious mind for other pursuits. Turn over as much of life's necessary and repetitive little tasks to unconscious habit as you can, James advises, and watch your mind and spirit soar.

John Kaag says James wanted to be somebody, to make his mark in the world, and that "makes being happy rather difficult." But James was always going to find happiness a challenge, ambitions or no. He knew intuitively that we are, as Aristotle said, the product of our habitual acts... (continues)

==

LISTEN (11.16.21.) Today in

This particular dance of transcendence should not be confused with Johnnny Depp's in that film...

Consciousness is complicated... (continues)

Thursday, November 18, 2021

Truth and consequences

“Strange is our situation here upon earth. Each of us comes for a short visit, not knowing why, yet sometimes seeming to divine a purpose. From the standpoint of daily life, however, there is one thing we do know: That we are here for the sake of others —above all for those upon whose smile and well-being our own happiness depends, for the countless unknown souls with whose fate we are connected by a bond of sympathy. Many times a day, I realize how much my outer and inner life is built upon the labors of people, both living and dead, and how earnestly I must exert myself in order to give in return as much as I have received and am still receiving.” Living Philosophies (via Chris Stevens, Northern Exposure)

the "bald-headed young Ph.D.'s" (ouch!) and their "desiccating and pedantifying" ways. His evident objection was not to their baldness, their youth, nor even their Ph.D.'s but to their cocksure belief in the exclusive primacy of an approach to philosophy that begins and ends in questions about the establishment of "certain knowledge" and insists on technicality and jargon at the expense of clarity for all except a very few specialists. James always declared himself on the side of experience, against "philosophy," wherever the latter had been shrunk to fit the limited dimensions or stylistic exclusivity of a "school" or discipline. He scorned some epistemologists' implicit view of reality as something necessarily twinned and correlated to whatever questions we happen at the moment to be asking about what and how we can know, as though abstract knowing were the highest purpose of life rather than one among many. SpringsKaag shares James's discomfort with narrow academic professionalism/pedantry, and the sense that being a "student of life's value and worth" is a larger mission than that of many students (read professors) of philosophy. "Philosophy lives in words, but truth and fact well up into our lives in ways that exceed verbal formulation." We're often encouraged to forget that, we profs, and to get on with the production of ever more verbalities and verbosities. In the process, as we were saying last time, we grow (in yet another colorful Jamesian phrase) "stone-blind and insensible" to life's simple joys and pleasures. (We'll read that soon in context, in "On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings.")

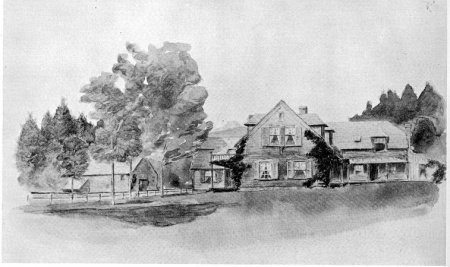

James's hallway (corridor) metaphor, treating pragmatism primarily as a method of negotiation and navigation among disparate interests and ends in philosophy and in life, reminds Kaag of James's beloved summer place in Chocorua with its fourteen doors "all opening outward." Pragmatism is a portal, not a sanctuary, "a place to dwell and meet the world" and maybe transcend it.

The distinction between truth and facts is crucial, for grasping the point of the pragmatic proposal that we reconstruct our conception of truth and our attitude toward it. "The facts may be out there, waiting for us to find them"--some of them--but the truth is our story about the facts"... and as we were saying in class yesterday, telling and acting from better stories about ourselves and the facts is an indispensable condition for creating a better society.

The free will story is prerequisite to the kind of optimism (meliorism) we need to face our most daunting challenges. "It holds up improvement as at least possible," it gives us a chance.

"The Gospel of Relaxation" has so impressed a friend that he now referes to it simply as "The Gospel," and I know instantly what he means. It's there that James speaks of the "buried life" or "inner atmosphere" of so many up-tight unhappy souls. Their Binnenleben has them too tightly wound. They need to let it go. Students need to relax before the big exam and trust their prior preparation, teachers need to relax in preparation for class and learn to "trust their spontaneity."

Back when I was still a struggling grad student, trying to figure out what I wanted to say about the philosophy of William James, I memorized this passage in Talks to Students ("On a Certain Blindness"):

Wherever a process of life communicates an eagerness to him who lives it, there the life becomes genuinely significant. Sometimes the eagerness is more knit up with the motor activities, sometimes with the perceptions, sometimes with the imagination, sometimes with reflective thought. But, wherever it is found, there is the zest, the tingle, the excitement of reality; and there is 'importance' in the only real and positive sense in which importance ever anywhere can be.

Tuesday, November 16, 2021

Moral Equivalence redux

LISTEN. AT&T is out again, I’m thumb-typing this on the phone. Do I get bonus points?

Another look at "Freedom and Life," chapter 2 in Sick Souls, Healthy Minds...

"Anhedonia," the inability to feel pleasure, is a strange condition indeed. Even the most miserably deprived sufferer must have some derivative notion of what it might be like to experience the cessation of pain. Wouldn't the contrast, even if only imagined, be pleasurable? But young James, on his Amazon voyage with Louis Agassiz in the late 1860s, turned "with disgust" from every imagined good. It appears he'd “just about touched bottom” well before that crisis diary entry in 1870.We've noted the life-saving impact on James of Renouvier's definition of free will, "the sustaining of a thought because I choose to when I might have other thoughts." He thought to try it, and was thus reborn as the prophet of pragmatic volition. It was a philosophical bootstrapping operation, as Kaag says, that defies common sense. "You can believe in free will by simply exercising your free will?"

"Always look on the bright side..." Practical advice, almost always. Believe that life is worth living, and see if your belief doesn't in fact help create the fact. Is this the power of positive thinking? Or of consistent willing? Or just of stubborn persistence? Again, what have you got to lose?

James's claim that most of his contemporaries would not have preferred to "expunge" the Civil War, even if they could do so without expunging its results, must strike many of us as strange. Or even perverse. But his point is that a hard-won victory is a thing to treasure and to inspire.

And in addition to an army enlisted "against Nature,” or those bits of nature and human nature that would defeat us, we’d better muster an army in defense of nature and against anthropogenic environmental destruction. Maybe something like what Naomi Klein and AOC have envisaged. The future is now.

Consciousness and transcendence

...We have been so long accustomed to the hypothesis of your being taken away from us, especially during the past ten months, that the thought that this may be your last illness conveys no very sudden shock. You are old enough, you've given your message to the world in many ways and will not be forgotten; you are here left alone, and on the other side, let us hope and pray, dear, dear old Mother is waiting for you to join her. If you go, it will not be an in harmonious thing. Only, if you are still in possession of your normal consciousness, I should like to see you once again before we part...

As for the other side, and Mother, and our all possibly meeting, I cant say anything. More than ever at this moment do I feel that if that were true, all would be solved and justified. And it comes strangely over me in bidding you good-bye how a life is but a day and ex presses mainly but a single note. It is so much like the act of bidding an ordinary good-night. Good-night, my sacred old Father! If I don t see you again Farewell! a blessed farewell! Your WILLIAM.I read that letter to my own dad, in his terminal summer following a diagnosis of leukemia. He got the message Henry may have missed, really so very simple: a message of gratitude and love, and an assurance that his message and presence would not by his children be forgotten. Not ever.

We read also today of Thoreau and his marvelous conclusion in Walden. "Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star." As a morning person, and a saunterer in the Thoreauvian spirit, and a dreamer of human intrepidity, I find in those lines great inspiration. I'm thinking of getting them inscribed in a visible and lasting way. Ask me about that next week.

James the "nitrous oxide philosopher" would have been intrigued by Michael Pollan's (and others') advocacy of research into the therapeutic potential of appropriately-prescribed hallucinogens.

HE has short hair and a long brown beard. He is wearing a three-piece suit. One imagines him slumped over his desk, giggling helplessly. Pushed to one side is an apparatus out of a junior-high science experiment: a beaker containing some ammonium nitrate, a few inches of tubing, a cloth bag. Under one hand is a piece of paper, on which he has written, "That sounds like nonsense but it is pure on sense!" He giggles a little more. The writing trails away. He holds his forehead in both hands. He is stoned. He is William James, the American psychologist and philosopher. And for the first time he feels that he is understanding religious mysticism.Mind-altering drugs may not afford deep metaphysical insight after all, but it's becoming increasingly clear that they can help PTSD sufferers (like war vets) and others whose pain is not amenable to mainstream pharmacology. James the humanist would agree.

James's summer home in Chocorua, New Hampshire was a wonderful getaway for him, and an apt metaphor for his philosophy and its anchoring temperament: "fourteen doors, all opening outwards." Like a transcendent consciousness, and (though the metaphors are mixed) like a flowing stream. James loved "the open air and possibilities of nature." Fling open the doors. Get out there. Even, or especially, in November.

Monday, November 15, 2021

Another chance

LISTEN. Another look at the Dilemma of Determinism today, in CoPhi (previously discussed in Happiness), and at John Kaag's "Determinism and Despair" chapter in Sick Souls, Healthy Minds: How William James Can Save Your Life.

The dilemma of this determinism is one whose left horn is pessimism and whose right horn is subjectivism. In other words, if determinism is to escape pessimism, it must leave off looking at the goods and ills of life in a simple objective way, and regard them as materials, indifferent in themselves, for the production of consciousness, scientific and ethical, in us... (continues)

We'd have to be pessimists, if we didn't think our various regrets might ever actually lead to constructive action on our part, to ameliorate the world's deficiencies and wrongs. We'd be conceding our permanent impotence in the face of its inexorable injustice. That's the left horn.

The right horn is subjectivism (not to be confused with subjectivity), which leaves us impotent and the world unjust but at least puts on a show "for the production of consciousness," gives us something to think about and deepens our appreciation of the deplorably un-closeable gap between how things are and how they should be.

That's a destructive dilemma, or for James it was. It was destructive of his volitional nature, his will to do something and not just think it. As John Lachs said, "There is something devastatingly hollow about the demonstration that thought without action is hollow, when we find the philosopher only thinking it."

Hollow is a good word for a world whose content is "indifferent" and whose actors are merely supposed to register sharp thoughts and feelings as they sit back and watch the gruesome play unfold. That's when, in Camus's later words, "the stage sets collapse" (cue Sisyphus and his stone) and a feeling of farce sets in. Intolerable farce, if you're James or a temperamental Jamesian. The future is then without "ambiguous possibilities," the play's denouement is already written, and we're just spectators.

No thanks, said James. Say I. That's "sick," in soul and solar plexus. A gut punch. Give us a universe of alternative possibilities and meaningful chances, let us improvise our lines, let us do and not just think and feel.

But of course it's in no one's power to give that, we must take it for ourselves. Take it upon ourselves to act as if that's our universe: a pluralistic world of possibilities and chances in which we can feel ourselves truly at home. “No fact in human nature is more characteristic than its willingness to live on a chance."

Taking chances means risking failure, accepting no guarantee of success, rejecting the dilemma of determinism and embracing our fallible melioristic opportunity to write a better ending.

Nevertheless there are unhappy men who think the salvation of the world impossible. Theirs is the doctrine known as pessimism.

Optimism in turn would be the doctrine that thinks the world's salvation inevitable.

Midway between the two there stands what may be called the doctrine of meliorism... Pragmatism Lec. 8

Speaking of better endings: we stuck with Andie McDowell and her daughter to the end of The Maid, after the unhappy middle acts. Alex and Maddy's chances look good. Isn't that all any of us can ask?

Thursday, November 11, 2021

Habit

"Do every day or two something for no other reason that you would rather not do it, so that when the hour of dire need draws nigh, it may find you not unnerved and untrained to stand the test.” That was once my rationale for rising at 5 a.m. Lately I wait for the first flicker of dawn, which these days (after the clocks fell back) is closer to 6. My biggest aversive daily effort now is probably my commute. Meetings, thankfully, are not a daily occurrence.

There is no more miserable human being than one in whom nothing is habitual but indecision, and for whom the lighting of every cigar, the drinking of every cup, the time of rising and going to bed every day, and the beginning of every bit of work, are subjects of express volitional deliberation. Full half the time of such a man goes to the deciding, or regretting, of matters which ought to be so ingrained in him as practically not to exist for his consciousness at all. If there be such daily duties not yet ingrained in any one of my readers, let him begin this very hour to set the matter right.Happiness does not coexist well with misery and contempt. If either shoe fits, do “set the matter right.” Don’t forget: “Any sequence of mental action which has been frequently repeated tends to perpetuate itself.” We really are what we habitually do.

There is no more contemptible type of human character than that of the nerveless sentimentalist and dreamer, who spends his life in a weltering sea of sensibility and emotion, but who never does a manly concrete deed. Rousseau, inflaming all the mothers of France, by his eloquence, to follow Nature and nurse their babies themselves, while he sends his own children to the foundling hospital, is the classical example of what I mean.

Wednesday, November 10, 2021

Maybe

LISTEN. Entering class today for the first time in the Covid era without a university-imposed mask mandate, in a red state and with shaky guidance from our school's president to "encourage our community members to consider the use of masks as circumstances warrant" and "encourage our students, faculty and staff who have not been vaccinated to consider taking this precaution."

Great. Do please consider it, all who've previously chosen to disregard minimal considerations of public health and responsible citizenship.

Wonder who was consulted about this.

But okay. Here we go.

That essay was based on James's lecture to the Harvard YMCA in 1895. Early provisional answer: maybe. Depends on the liver.

Before century's end he was offering a less equivocal answer, in "On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings":

"Crossing a bare common," says Emerson, "in snow puddles, at twilight, under a clouded sky, without having in my thoughts any occurrence of special good fortune, I have enjoyed a perfect exhilaration. I am glad to the brink of fear."

Life is always worth living, if one have such responsive sensibilities. But we of the highly educated classes (so called) have most of us got far, far away from Nature. We are trained to seek the choice, the rare, the exquisite exclusively, and to overlook the common. We are stuffed with abstract conceptions, and glib with verbalities and verbosities; and in the culture of these higher functions the peculiar sources of joy connected with our simpler functions often dry up, and we grow stone-blind and insensible to life's more elementary and general goods and joys.

The remedy under such conditions is to descend to a more profound and primitive level. To be imprisoned or shipwrecked or forced into the army would permanently show the good of life to many an over-educated pessimist. Living in the open air and on the ground, the lop-sided beam of the balance slowly rises to the level line; and the over-sensibilities and insensibilities even themselves out. The good of all the artificial schemes and fevers fades and pales; and that of seeing, smelling, tasting, sleeping, and daring and doing with one's body, grows and grows. The savages and children of nature, to whom we deem ourselves so much superior, certainly are alive where we are often dead, along these lines; and, could they write as glibly as we do, they would read us impressive lectures on our impatience for improvement and on our blindness to the fundamental static goods of life. "Ali! my brother," said a chieftain to his white guest, "thou wilt never know the happiness of both thinking of nothing and doing nothing. This, next to sleep, is the most enchanting of all things. Thus we were before our birth, and thus we shall be after death. Thy people. . . . when they have finished reaping one field, they begin to plough another; and, if the day were not enough, I have seen them plough by moonlight. What is their life to ours,—the life that is as naught to them? Blind that they are, they lose it all! But we live in the present."(11)

The intense interest that life can assume when brought down to the non-thinking level, the level of pure sensorial perception...

And this is James's great theme, on my reading: immediacy, supported by perception and constant attentiveness to novelty and possibility in our experience. It is immediacy that calls us out to ourselves for analyzing too much and appreciating too little, for brooding too much and forgetting how lucky we are, for fabricating too much instead of exploring and discovering. Immediacy applies the brakes to unchecked speculation and subjectivist rumination.

But philosophers in our tradition must also think about immediacy, as well as consult it. Which gets priority? Neither. It's a circular dance, without a lead partner.

My friend in Alabama who's spent a career worrying "the problem of the criterion" finds such irresolution annoying and intolerable. I find it merely emblematic of pragmatism and the human condition. It's the best we can do. It might be good enough. Maybe.

Maybe too, on the heels of Carl Sagan's birthday, we can ponder our lucky stars from a cosmic perspective. We're star stuff. What a wondrous world we've awakened to. There's no place like home.

Tuesday, November 9, 2021

Moral Equivalence

LISTEN. "The war against war is going to be no holiday excursion or camping party," begins James's "Moral Equivalent of War." This is no idle metaphysical dispute about squirrels and trees, it's ultimately about our collective decision as to what sort of species we intend to become. It's predicated on the very possibility of deciding anything, of choosing and enacting one identity and way of being in the world over another. Can we be more pacifistic and mutually supportive, less belligerent and violent? Can we pull together and work cooperatively in some grand common cause that dwarfs our differences? Go to Mars and beyond with Elon, maybe?

It's Carl Sagan's birthday today, he'd remind us that while Mars is a nice place to visit we wouldn't probably want to live there. Here, on this "mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam," is where we must make our stand. Here, on the PBD. The only home we've ever known.

In light of our long human history of mutual- and self-destruction, the substitution for war of constructive and non-rapacious energies directed to the public good ought to be an easier sell. Those who love the Peace Corps and its cousin public service organizations are legion, and I'm always happy to welcome their representatives to my classroom. Did that just last year.

But the idea of sacrificing personal financial gain for the opportunity of a lifetime to immerse in another culture and lend tangible life-support for our fellow human beings is not immediately enticing to most of those who've been raised to value personal acquisition over almost all else. Have we lost our appetite for peace? Have we become inured to war? Do we just want to score an early Black Friday deal?

James didn't think so. Or wouldn't have, re: Black Friday, though he did already cringe (in that '06 letter to H.G. Wells, who he cites in Moral Equivalence) at the commercial Bitch-goddess "values" of our cash-besotted society. He "devoutly believes" in a pacifistic future for humanity, or maybe really just believed in believing in it. That's a start.

A non-military conscription of our "gilded youth" would be good for them and for us all, so many of the great non-gilded majority already effectively "conscripted" by circumstance to enlist not in a noble cause but for a crummy paycheck. You don't really get to be all you can be, in today's Army. But tomorrow's could be mustered to fight not "against Nature" but (for once) for it, and for our continued place in it. We could choose to battle the consumer lifestyle that has fueled anthropogenic climate change.

Yuval Noah Harari seems to me to be on James's wavelength when he says "the story in which you believe shapes the society that you create." If we believe we can successfully battle our own worst "Onceler" impulses, that "fiction" stands a fighting chance of becoming fact. If we don't, it doesn't. Apocalyptic fatalism is not constructive.

James's old student Morris Raphael Cohen once attempted to persuade James that baseball could be the sort of moral equivalent he was looking for, a way of channeling our martial impulses into benign forms of expression on playing fields, in harmless competition. James wasn't having it. "All great men have their limitations," Cohen sighed. ("Baseball as a National Religion")Monday, November 8, 2021

Play on

We were honored to participate last night in her memorial commemoration at Unity Village near here, with music and poetry and a scattering of ashes amongst the flowers. Her life of service and nurture and kindness inspire like the rose, reaching for the light but keeping rooted in the soil of this earth. That example has not sailed over our human horizon, though there was talk last night of a "transition" and a departure to another realm. For myself at least, she's still right here. Her goodness blooms like the rose. --Jy 15, '21

"I wish I'd known enough to ask my teachers the right questions before they died," Neiman laments. My dad was my earliest teacher-by-example, as I'm sure many of us would say. I'm so glad I had the opportunity to ask him all the questions I'd long put off posing, in what we knew would be the final months of his life back in the summer of 2008. Ask your questions. Write that script.

"Most people grow happier as they grow older." The data support that, we've learned in Happiness class, even though most of us know a grumpy old person or two. The U-Bend varies, in different places. The Swiss start aging happily at 35, the Ukrainians not 'til 62. But happier days await most of us, say the stats.

"Growing up means realizing that no time of one's life is the best one," just as each season of the year brings its own unique joys. "To be interested in the changing seasons is, in this middling zone, a happier state of mind than to be hopelessly in love with spring." George Santayana, "perfection of rottenness" and all, was right about that.

Leibniz thought most people would choose on their deathbed to live their lives again only on the condition that they would be different next time. Nietzsche thought that was cheating, but Bill Murray arranged it in Groundhog Day (and won Andie McDowell's heart). I like David Hume's attitude: I might not want to repeat everything I recall of the last decade, but I'm banking on the next one being better. Give me ten more unscripted years and I'll take my chances.

Thursday, November 4, 2021

Taking chances

Remember when old December s darkness is everywhere about you, that the world is really in every minutest point as full of life as in the most joyous morning you ever lived through; that the sun is whanging down, and the waves dancing, and the gulls skimming down at the mouth of the Amazon, for instance, as freshly as in the first morning of creation; and the hour is just as fit as any hour that ever was for a new gospel of cheer to be preached. I am sure that one can, by merely thinking of these matters of fact, limit the power of one s evil moods over one s way of looking at the Kosmos. Letters, vol.1

That's still Stoicism, but it's also humanism and a hint of what he would soon come to regard as the essence of freedom. Control your attention, entertain the specific and more constructive thoughts you choose when you might have other lesser thoughts. Be free in your mind, attend to what you will. Don't surrender to incursive and debilitating thoughts and moods. Don't concede determinism, which for James meant a pre-determined "future with no ambiguous possibilities," a block universe fixed and unalterable "from eternity" as (according to some) an implacable consequence of Darwinian evolution.

James was a Darwinian, declaring himself opposed to "the Christian scheme of vicarious salvation" and "wedded to a continuously evolutionary" view but not a believer in implacable consequences. He thought Darwin's bulldog Huxley went too far towards embracing causal determinism and abandoning free will. James wanted a pluralistic universe of alternative possibilities and meaningful chances. In Varieties he would also write:

“No fact in human nature is more characteristic than its willingness to live on a chance. The existence of the chance makes the difference… between a life of which the keynote is resignation and a life of which the keynote is hope.”

And that's the difference between sick souls and healthy minds: the difference between resignation and hope. James understood both attitudes, had lived them both alternately and repeatedly. His life was a long series of vacillations between those antipodal poles, but he always managed to swing back to the sunny side. He returned to life and restored its music, reversing the "falling dead of the delight" and restoring the spirits of the "melancholy metaphysician" again and again. We who were not blessed to be happily "once-born" (and thus delivered to lives of uninterrupted bliss) can relate to his swings and returns. Possibly, they can teach us something valuable about happiness.

One of our discussion questions in Happiness today: Does life lose zest and excitement, if things were foredoomed and settled long ago?

A student responds:

Interesting analogy. When reading a story whose ending we don't want to "spoil" we pretend, page by page, that the outcome is still really unresolved and that what happens in the subsequent unfolding of the tale will "determine" what ultimately happens. Don't we? We pretend, in other words, that the story has not already been entirely writ. We try to block out any awareness of an AUTHOR, whose existence would imply a PLOT and a PLAN (or SCHEME) which the characters in the story have no power to influence. We want those characters' actions to contribute to the determination of events. That's what makes a story compelling to us. James would say that's what makes life compelling too. We're all authors here, in a pluralistic and unfated world. Turn the page."I would definitely say so. What’s the point of caring if nothing I do changes the outcome? Well, I suppose I’m just destined to care, then? Really, this whole debate becomes muddied with these types of infinite back-and-forths.

Now, I don’t think a radical determinism necessarily removes all excitement (Well, unless if it’s destined to). My point is that one can think of it as a book. The ending of the book doesn’t change as you read it. No, it remains the same at every twist and turn of the plot. However, the reader remains engaged and on the edge of their seat the entire time. So, could a predestined life not be just as excitable?"

Wednesday, November 3, 2021

Meaningful work

In a truly humane society, said Marx, we'd hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, and do philosophy ("criticize") after dinner. (And rear cattle?) Hmmm. That really doesn't sound like utopia. I'd rather be reading, walking, biking, talking, and eating someone else's catch in the evening. As for philosophizing, that would be more-or-less constantly in the air.

But most jobs don't rise to the level of work in this honorific sense, said Growing Up Absurd author Paul Goodman, they're mostly useless, harmful, wasteful, demeaning, and dumb. That was in 1960, already, on the cusp of the New Frontier. "Is it possible, how is it possible, to have more meaning and honor in work? to put wealth to some real use? to have a high standard of living of whose quality we are not ashamed? to get social justice for those who have been shamefully left out? to have a use of leisure that is not a dismaying waste of a hundred million adults?”

Is there a realistic alternative? Can we learn to consume wisely, and not be consumed by things? We must, for "our present conditions are unfit for grown-up human beings."

Tuesday, November 2, 2021

Stay

On the last day of April, 1870, he recorded a new diary entry: " I think that yesterday was a crisis in my life. [He'd been having a lot of those!] I finished the first part of Renouvier's 2nd Essay and saw no reason why his definition of free will-- the sustaining of a thought because I choose to when I might have other thoughts-- need be the definition of an illusion. At any rate, I will assume for the present-- until next year-- that it is no illusion. My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will."

And: "Today has furnished the exceptionally passionate initiative... needful for the acquisition of habits."

On Feb. 6, 2014 John Kaag, a young post-doc scholar at Harvard who'd been languishing in his own sea of despond, happened on the scene of a horrific tragedy. A young man named Steven Rose, about the age James had been when he confided his own crisis in that diary entry, leapt to his death from the observation deck of William James Hall.

He may have been one of those given to "too much questioning and too little active responsibility," resulting in deep pessimism and a hopeless view of life. Who knows?

We do know, though, that identifying and fighting actual problems and challenges to lives worth living is itself a source of "cheerfulness" and self-strengthening resolve.

And we know there's reason to suspect far more in heaven and earth than is typically dreamt of in our normal waking consciousness. The dog on my lap hasn't a clue about such things, and yet we share a life-world. Of what wonders may we be similarly clueless?

James doesn't know, nor do we. The point is to remain in touch with the "deepest thing in our nature," which deals with possibilities rather than finished facts. That "dumb region of the heart" is smarter than we know.

So we'll discuss that feeling of being "pulled in too many directions" and why, for those who feel that way, philosophy can't just be a "detached intellectual exercise." Philosophical arguments (such as free will vs. determinism) must "vivify" and point away from darkness and stasis, to matter at all.

Can belief that life is worth living become self-fulfilling? James said it could. But as Tim McGraw's dad Tug's old rallying slogan said, you gotta believe. You gotta believe.

"Is life worth living?" Maybe. But that implies maybe not. Can we, should we ever say that? Ask your doctor, the cartoon on my door advises, if a longer life is right for you. But no: ask yourself.

Monday, November 1, 2021

The best years

Education, travel, and work at their best all "undercut the dogmatism of the worldviews into which we are born." That's the project of a lifetime. Not learning, not going, not finding something valuable to do with your time all block it. Sadly, many are blocked early and never get going. Many get stuck replicating the choices and limited opportunities demonstrated by their parents. But "if you don't reject any of their choices you are not grown-up." And if you won the parent-lottery, you'll find plenty of their choices to have been spot-on. Not all, though.

Learn some languages and learn to love music early on, is something I wish the adults in my life had been more insistent about. They gave me a good model of fluent English, and bought me a piano and lessons. But I wanted to play ball during lesson-time. Coulda done both, with the right cajoling. Or incentives. They used to give me dollars for A's, why not for sticking with Mrs. Boas?; and then her successor whose name now escapes me and who I resented, ironically I now see, because lesson time coincided with the first half of my favorite TV show: Glen Campbell. John Hartford was great on that.

Neiman has interesting things to say about books, which "make you think differently about love and loss and integrity," and the book of the world, which as Augustine said is sadly neglected by so many who know only one page. Travelers are readers of the great world-book. Stay-at-homes mistake their own cultural assumptions for the whole of reality. They do not dwell in possibility, their actuality is stunted.

Best way to travel is still on shanks' mare. Those who do not walk, said Rousseau, are like "prisoners in a small closed-up cage." If you want to understand where you are, you've got to get away. In your mind, anyway. Isn't that what the poet meant when he talked about not ceasing from exploration?

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time...