In A&P we close Michael Ruse's A Meaning to Life. His Victorian-inspired wit and occasional glibness is not to everyone's taste. Richard Dawkins, Ruse delights in telling us, is not a fan. But I really like the way Ruse wraps his story up with this sage advice, regarding the search for Ultimate Meaning:

Don't spend your life agonizing about this or letting people manipulate you with false promises. Think for yourself, as my Quaker mentors insisted. Life here and now can be fun and rewarding, deeply meaningful. [Note the lower-case m.] Remember, (David) Hume didn't just play backgammon [when his metaphysical researches left him despondent and confused] -- he dined, he conversed, he was "merry with my friends." Like I said: a nice cup of tea, or perhaps a single malt, and a chat. With my beloved graduate students and Scruffy [his dog -- see jacket illustration] joining in the conversation! Live for the real present, not the hoped-for future. Leave it at that.I think Professor Ruse must also, like me, be a fan of the end of the film Monty Python's Meaning of Life.

Well, it's nothing very special. Uh, try and be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try and live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations...And,

Ruse's A Meaning to Life concludes poetically, "In the woods" with George Meredith's salute to "the lover of life [who] sees the flame in our dust/ And a gift in our breath."

My mentor John Lachs is one of those. In his In Love With Life: reflections on the joy of living and why we hate to die Lachs celebrates life and, in the spirit of Martin Hagglund's This Life and the resonant keynote of our odd semester, its glorious finitude.

We can be grateful to be alive and we can enjoy the surge of energy in the struggle for moments of meaning and light. In this way, though we may not always make love to life or prevail over force and circumstance, we can at least glory in the effort and feel fully alive.

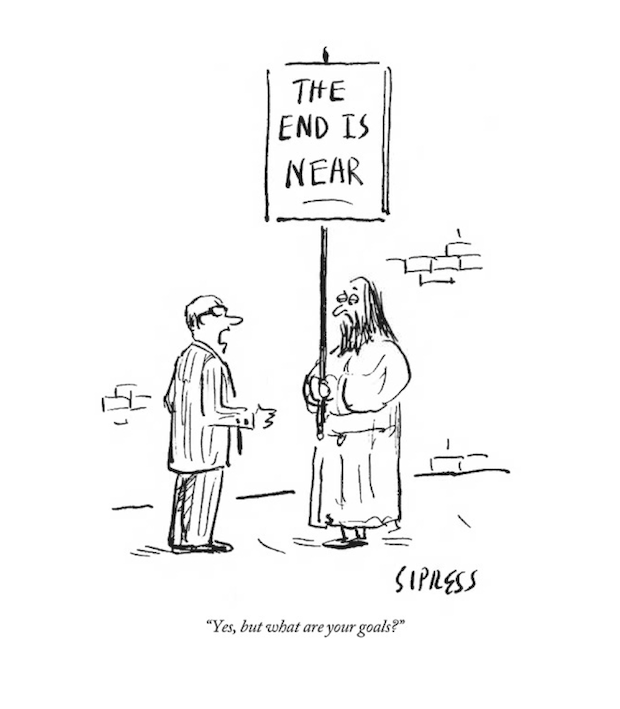

The effort of living and the vital feeling of life (cue Mister Rogers, "it's a great feeling" etc.) are what motivate the cartoon figure to confront the sign-carrying apocalypse-monger who insists The End is Near with an impatient demand: "Yes, but what are your goals?"

Peter Singer, facing the threat of apocalypse, would ask that question too. He is the last philosopher in our Little History. A self-described "professor of bioethics with a background in philosophy" and a utilitarian who never stops wondering what he and we can do to optimize happiness and minimize misery, he insists that we think hard about animal suffering, saving all the lives we can, doing the most good we can, and generally about living ethically in the real world. He's hard to answer, like Socrates. Also like Socrates, he's unpopular with those who take his challenges personally. Unlike Socrates, to his great good fortune, he'll not be fatally persecuted for his questions and their implicit rebukes.

Turing and Searle represent the debate between those who hope and expect that artificial intelligence will continue to evolve and to enhance and perhaps even complete our lives, and those who are sure (or at least counter-hopeful) that it won't and can't. Should we be so certain that our own consciousness was emergent from biological conditions not conceivably replicable in silicon? Don't ask me. Ask Her. Ask Alan Watts 2.0. But maybe don't ask Dr. Caster of Transcendence, if that's the virtual afterlife I don't want to go.

John Rawls is the social contractarian who proposes that we think about principles of justice from behind a veil of ignorance, so as to eliminate special pleading and personal prejudice. If you don't know who you are, you won't know what's in it for you to support this or that policy or program or theory of justice. But will you know enough to care about anything at all?

Not sure why the Swiss in particular are chosen here for unveiled criticism, inequity is at least as great in the U.S.

As for caring, on either side of the veil: Rawls himself cared a great deal about baseball. This is a subject I may want to pursue, for this year's Baseball in Literature and Culture Conference in Kansas. Time to come up with a submission. Would a veil help? And what would Rawls say about the present state of financial compensation and free agency in his favorite game? Is the income gap between Red Sox players and Fenway spectators something his Difference Principle could rationalize and accept as better for the "least well-off" fans in the stands?

"Baseball is the best of all games," Rawls told a friend.

First: the rules of the game are in equilibrium: that is, from the start, the diamond was made just the right size, the pitcher’s mound just the right distance from home plate, etc., and this makes possible the marvelous plays, such as the double play. The physical layout of the game is perfectly adjusted to the human skills it is meant to display and to call into graceful exercise. Whereas, basketball, e.g., is constantly (or was then) adjusting its rules to get them in balance.

Second: the game does not give unusual preference or advantage to special physical types, e.g., to tall men as in basketball. All sorts of abilities can find a place somewhere, the tall and the short etc. can enjoy the game together in different positions.

Third: the game uses all parts of the body: the arms to throw, the legs to run, and to swing the bat, etc.; per contra soccer where you can’t touch the ball. It calls upon speed, accuracy of throw, gifts of sight for batting, shrewdness for pitchers and catchers, etc. And there are all kinds of strategies.

Fourth: all plays of the game are open to view: the spectators and the players can see what is going on. Per contra football where it is hard to know what is happening in the battlefront along the line. Even the umpires can’t see it all, so there is lots of cheating etc. And in basketball, it is hard to know when to call a foul. There are close calls in baseball too, but the umps do very well on the whole, and these close calls arise from the marvelous timing built into the game and not from trying to police cheaters etc.

Fifth: baseball is the only game where scoring is not done with the ball, and this has the remarkable effect of concentrating the excitement of plays at different points of the field at the same time. Will the runner cross the plate before the fielder gets to the ball and throws it to home plate, and so on.

Finally, there is the factor of time, the use of which is a central part of any game. Baseball shares with tennis the idea that time never runs out, as it does in basketball and football and soccer. This means that there is always time for the losing side to make a comeback. The last of the ninth inning becomes one of the most potentially exciting parts of the game. And while the same sometimes happens in tennis also, it seems to happen less often. Cricket, much like baseball (and indeed I must correct my remark above that baseball is the only game where scoring is not done with the ball), does not have a time limit. Boston Review

Kurt Andersen says the right has now effectively raised two generations of "fair and balanced" Fox-watchers who discount all facts that contradict their opinions. That was a joke, back in grad school: "Discard all facts that dispute your theory," was the parody principle with which we mocked our own earnest seriousness. Now it's evidently the new "norm"... how SAD.

It's evident that the incumbent POTUS understands very little of the machinery and purpose of shared governance. And yet he seems to have understood "better than almost everybody" that "the breakdown of a shared public reality built upon widely accepted facts" is a golden opportunity for his variety of huckster hustler politics, under cover of the "Don't even think about it..." mantra.

UCONN's Michael Lynch is one of the most astute observers of these truth-discounted times, and of the crucially enabling role played by the Internet in diluting our commitment to a "shared public reality." In The Internet of Us he writes.

My hypothesis is that information technology, while expanding our ability to know in one way, is actually impeding our ability to know in other, more complex ways; ways that require 1) taking responsibility for our own beliefs and 2) working creatively to grasp and reason how information fits together... greater knowledge doesn't always bring with it greater understanding.We're glutted with information, much of it false or irrelevant, while starving for wisdom and integrity. The "gods of silicon valley" will have much to answer for, if they don't step back from their unexamined support of authoritarianism in the public sphere (gathering and disseminating user data for the benefit of self-interested politicians, providing a ready and eagerly-neutral platform for all kinds of misinformation and outright lies, etc.)

But there's good news: it can't get much worse, we're surely at Peak Fantasy now. Aren't we?

The final installment of American Philosophy: A Love Story reveals William Ernest Hocking's possibly illicit fantasy love interest, the Nobel novelist Pearl S. Buck. She declared herself "weary unto death" of proselytizing hypocritical American fundamentalist missionaries in China. Much like Barbara Kingsolver's later tale of missionaries in the Congo, she thought the do-gooders did far more harm than good when condescending to their "lost sheep." We'd all do better to listen and learn what we can from one another, rather than trying so hard to win converts to our own POV.

Gabriel Marcel was the French Existentialist (and fan of Hocking) who, contrary to the more prominent rockstars Sartre, de Beauvoir, and Camus, did believe in God. He said “life is not a problem to be solved but a mystery to be lived." Can't it be both? But he and his atheist counterparts did agree that philosophy must begin in actual human experience and "the concrete stuff of life," not in airy theoretical abstractions.

The dead are gone, in body, and many of us also doubt their presence in any form of supernatural spirit. But their memories, legacies, and (for those who committed their thought to print) words may persist. Is it some sort of ancestor cult that engages those thoughts and continues the conversation with the old dead philosophers?

No. We mustn't worship them, but why wouldn't we want to conduct a virtual dialogue with the wisest of the dead? Human finitude may be tragic but it needn't be a total loss. The dead and the living may continue to commune together. What else is a library but a gathering place for secular (though in its bibliophilic/philosophic way sacred) communion? Kaag's response to Royce's last written words is quite poignant on this point.

John Kaag ends his book where he began it, retutrning to the question of whether life is truly worth living. How do you "live a creative, meaningful life in the face of our inevitable demise"? His answer may strike some as disappointingly equivocal. It's been suggested that "maybe" is not so good an answer to that question as "possibly," with the latter's emphasis more hopeful and encouraging.

John Kaag ends his book where he began it, retutrning to the question of whether life is truly worth living. How do you "live a creative, meaningful life in the face of our inevitable demise"? His answer may strike some as disappointingly equivocal. It's been suggested that "maybe" is not so good an answer to that question as "possibly," with the latter's emphasis more hopeful and encouraging.

That's as may be, but the publication of Kaag's latest book Hiking With Nietzsche: On Becoming Who You Are gives strong indication that his "maybe" is as positive an affirmation as can be. As Nietzsche expressed it: "The formula of my happiness: A Yes, a No, a straight line, a goal." And as Viktor Frankl quoted Nietzsche in Man's Search for Meaning, "He who has a why to live can endure almost any how." The peripatetic life is the how of choice, for Kaag as it was for Nietzsche (who said all great thoughts are conceived while walking). "Walking is among the most life-affirming of human activities. It is the way we organize space and orient ourselves to the world at large. It is the living proof that repetition--placing one foot in front of the other--can in fact allow a person to make meaningful progress." Emerson, who was one of Nietzsche's heroes, agreed. "Each soul, walking in its own path, walks firmly..." So: walk your path.

And finally, as Kaag puts it in the last paragraph of his Acknowledgements, the project at West Wind, the recovery of love and purpose, and especially the birth of his daughter have all converged to restore for him the "zest" the makes life so very worth living. Zest awaits us all. Even in Fantasyland.

==

So, any last words this semester?

“There is no conclusion. What has concluded, that we might conclude in regard to it? There are no fortunes to be told, and there is no advice to be given. Farewell."

Great exit line, Professor James, but I can't agree. Don't conclude prematurely is itself good advice. The Pythons had good advice too. "Try and be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try and live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations.”

Uncle Albert offers the best advice of all: simply don't stop questioning.

“Don't think about why you question, simply don't stop questioning. Don't worry about what you can't answer, and don't try to explain what you can't know. Curiosity is its own reason. Aren't you in awe when you contemplate the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvelous structure behind reality? And this is the miracle of the human mind--to use its constructions, concepts, and formulas as tools to explain what man sees, feels and touches. Try to comprehend a little more each day. Have holy curiosity.”

“Don't think about why you question, simply don't stop questioning. Don't worry about what you can't answer, and don't try to explain what you can't know. Curiosity is its own reason. Aren't you in awe when you contemplate the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvelous structure behind reality? And this is the miracle of the human mind--to use its constructions, concepts, and formulas as tools to explain what man sees, feels and touches. Try to comprehend a little more each day. Have holy curiosity.”And keep you eyes on the goal.

LISTEN 12.2.19