LISTEN (recorded November 2019, this was originally posted for our Philosophy of Happiness class's discussion of Epicureanism). It's our penultimate lesson in how to be an Epicurean, today in Happiness, with the chapters on "Science and Scepticism" and "Social Justice." (And, sneak peaks of reports on Stoicism and Watts redux, and a surprise.)

"Our life has no need now of unreason and false opinion," but now more than ever that's what we have in spades. See yesterday's dawn mention of Kurt Andersen's "

plunge" into the Fox abyss, and

Moscow Marsha, and really just about everything in the headlines over the last several years. Will we ever get out of

Fantasyland? Maybe, when

Fred Rogers's children take the lead.

Or we could just accept the atomic premise that most of what happens depends on the swerving "little particles" over whose movements we exercise minimal control. But we can save that discussion for the last chapter - "Should I be a Stoic instead?"

Meanwhile, convenient as it would be for those of us in the most egregiously emitting nations to do so, we can't afford the luxury of accepting things like climate change as entirely beyond the scope of our involvement. We have a moral responsibility to seek solutions. Being an epicurean does not mean retiring to our respective gardens and awaiting the apocalypse. What would

Thomas Jefferson do?

What he said was:

I too am an Epicurean. I consider the genuine (not the imputed) doctrines of Epicurus as containing every thing rational in moral philosophy which Greece & Rome have left us. Epictetus indeed has given us what was good of the Stoics; all beyond, of their dogmas, being hypocrisy and grimace. their great crime was in their calumnies of Epicurus and misrepresentations of his doctrines: in which we lament to see the candid character of Cicero engaging as an accomplice. the merit of his philosophy is in the beauties of his style. diffuse rapid, rhetorical, but enchanting. his prototype Plato, eloquent as himself, dealing out mysticisms incomprehensible to the human mind, has been defied by certain sects usurping the name of Christians; because, in his foggy conceptions, they found a basis of impenetrable darkness whereon to rear fabrications as delirious, of their own invention...I do love the Monticello Sage's Plato-bashing here, notwithstanding the latter's truly admirable and visionary gender utopianism. But one of chapter 12's epigraphs does make things uncomfortable for a Jeffersonian: "A free life cannot acquire great wealth, because the task is not easy without slavery..." He kept his slaves but squandered much of his wealth on books and wine. We hold these truths to be self-evident... Noble words, ignoble deeds.

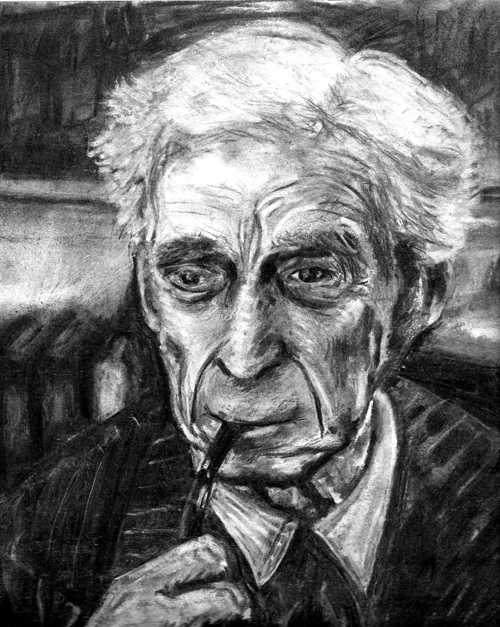

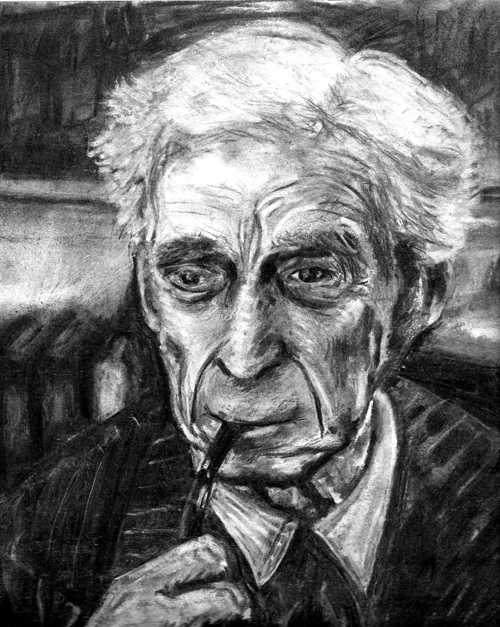

Was Marx an Epicurean at heart? His youthful ideal "society of the future would be recreational and allow for individual whims and preferences," like Bertrand Russell's. He too was an epicurean, of sorts. But his critics will remind us, he also said "better red than dead."

In a world where no one is compelled to work more than four hours a day, every

person possessed of scientific curiosity will be able to indulge it, and every painter will be able to paint without starving, however excellent his pictures may be. Young writers will not be obliged to draw attention to themselves by sensational potboilers, with a view to acquiring the economic independence needed for monumental works, for which, when the time at last comes, they will have lost the taste and the capacity.

[…]

Above all, there will be happiness and joy of life, instead of frayed nerves, weariness, and dyspepsia. The work exacted will be enough to make leisure delightful, but not enough to produce exhaustion. Since men will not be tired in their spare time, they will not demand only such amusements as are passive and vapid. At least 1 per cent will probably devote the time not spent in professional work to pursuits of some public importance, and, since they will not depend upon these pursuits for their livelihood, their originality will be unhampered, and there will be no need to conform to the standards set by elderly pundits. But it is not only in these exceptional cases that the advantages of leisure will appear. Ordinary men and women, having the opportunity of a happy life, will become more kindly and less persecuting and less inclined to view others with suspicion. The taste for war will die out, partly for this reason, and partly because it will involve long and severe work for all. Good nature is, of all moral qualities, the one that the world needs most, and good nature is the result of ease and security, not of a life of arduous struggle... "In Praise of Idleness" [

b'p]...

Russell on the value of philosophy for life

Some questions: Is Epicurean scepticism peculiarly well-suited to this moment in history?Will we ever, or should we even desire to, explain everything in terms of micro-phenomena?

Should an Epicurean concerned about climate change become an activist? Should calculations of personal happiness and the enjoyment of one's own life be decisive for him/her in addressing that question? Is it self-destructive to affirm "the view that the fate of all plants, animals and humans resides with a loving and intelligent deity?