It’s Thought Experiment day in CoPhi (TX-Phi?) with Philippa Foot’s infamous runaway trolley, Judith Thomson‘s unwanted violinist (always a hot topic in Bioethics), and John Rawls‘ Veil of Ignorance in LH (&

Jonathan Wolff on Rawls in PB); and in

AtP,

Bill Moyers and

Joseph Campbell. [And for #H1 on Tuesday, a peek forward at

Peter Singer.]

And here's a PB bonus on the

Trolley Problem... more

trolley problems... plus, Sarah Bakewell's recent

Times "trolley-ology" review.... (What would

Montaigne say about the Fat Man? Maybe

“I just don’t do trolleys.” )

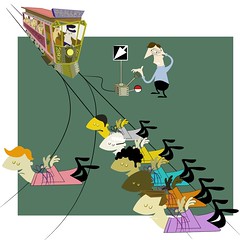

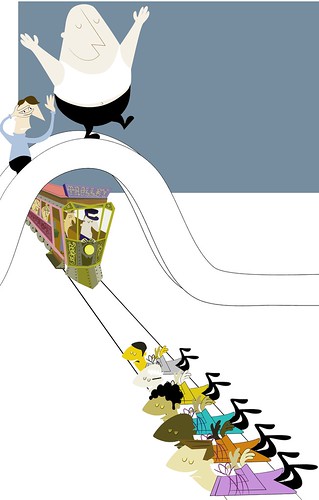

For those who do trolleys, two scenarios seem to pull in different directions: either pull a switch to divert the runaway trolley, or push a person fatally into its path. Same result, different intuitions about our moral culpability.

In numerical terms, the two situations are identical. A strict utilitarian, concerned only with the greatest happiness of the greatest number, would see no difference: In each case, one person dies to save five. Yet people seem to feel differently about the “Fat Man” case. The thought of seizing a random bystander, ignoring his screams, wrestling him to the railing and tumbling him over is too much. Surveys suggest that up to 90 percent of us would throw the lever in “Spur,” while a similar percentage think the Fat Man should not be thrown off the bridge. Yet, if asked, people find it hard to give logical reasons for this choice. Assaulting the Fat Man just feels wrong; our instincts cry out against it.

I find it hard to take trolleys seriously. But there is a point to thinking about cartoonishly-exaggerated ethical scenarios...

What is the point of thought experiments? (What is the point of armchairs?) To “trigger our awareness of conflicts between judgments that we previously held in combination” and “open up new conversations.” And give us a relaxed venue for mulling stressful situations, so we'll be prepared for the them if and when they come. Mostly thought experiments are just fun.

One result of trolley experiments is the valuable reminder that concrete choices, in even the most contrived, improbable situations, are messy and complicated. A normally-endowed and emotionally healthy human being will never find it easy to pull a switch that kills, no matter what she tells you.

A cool utilitarian calculus has its place, and so do our subrational instinctive juices. If either were missing, we would make some truly terrible choices. Yet there is also still room for that quaint seated figure, thinking through the principles and working out a kind of pragmatic yet justifiable wisdom. An armchair is also a useful place for reading books [about thought experiments]. With all this help, then perhaps when the trolley comes rattling around the corner, and with a half-second to decide, you might just do the right thing. Whatever that may be. Bakewell

What principles of social justice would be chosen by parties thoroughly knowledgeable about human affairs in general but wholly deprived—by the “veil of ignorance”—of information about the particular person or persons they represent? Rawls thought they’d pick these two: (1) fundamental individual equality, allowing (2) only those inequalities that can be presumed to work out to everyone’s advantage.

An amusing (if not especially animated) rendition of Rawls:

Last time we talked Rawls somebody suggested a sporting example: a Rawlsian social contract won’t entirely level our playing fields, won’t be purely egalitarian. Behind the veil we’d probably want to design a society in which those who excel at a game others might enjoy watching, for instance, will have sufficient incentive to actually play. The basketball fan does not begrudge Michael Jordan’s fortune, if he thinks it contributes to his own delight at courtside. It’s to his “advantage,” too, for Michael to have more money and notoriety.

But whatever the deliberators decide, behind that veil, Rawls wanted to give them a procedural opportunity to agree on the basis of relevant considerations. We’ve instead been auctioning public office and social influence to the highest, loudest bidders, not the coolest reasoners. There’s nothing fair or just about that. The “law of peoples” can do better.

Michael Sandel is a semi-Rawlsian, with his talk of restoring respectful forms of democratic argument. He's also, as Wolff notes, "a communitarian who thinks Rawls is biased towards liberal individualistic conceptions of the good."

And he likes to think about trolleys too.

The late Robert Remini, biographer of Jackson and Clay, was by my reckoning a Rawlsian in spirit.

He bemoaned the lost art of political compromise. (“Clay,” btw, is a family namesake: my Dad was James Clay, his Dad was Clay, and back it went deep into the 19th century. A rooted source of my pragmatic attraction to anti-ideology, perhaps?) [Remini on NPR]

An important question: "who's doing the imagining in the Original Position?" A bunch of philosophers will presumably think and deliberate differently from a bunch of fascists, or monks. But if it's a polyglot mix drawn from a diverse society, and none of them knows their race, sex, earning power, or basic preferences, maybe they won't think exclusively like (narrow or partisan) philosophers, fascists, and monks. Maybe they'll think like pluralists and cosmopolitans. Maybe they won't be prepared to gamble with their liberty. Maybe they'll want to be just and fair, and be more inclined to take care of the least well-off. Maybe so.

Carlin Romano fills out Rawls's position with the important, astonishing, neglected biographical Rawls back-story. It's useful and illuminating to know who he is, in assessing his theory of justice. He was a lucky child, recovering from diptheria and pneumonia, then a lucky soldier. His siblings and army brothers were not so lucky. He felt bad about his good luck, and angry about the theodicies offered to account for it.

A Lutheran pastor... said that God aimed our bullets at the Japanese while God protected us from theirs. I don't know why this made me so angry, but it certainly did. I upbraided the Pastor (who was a First Lieutenant) for saying what I assumed he knew perfectly well... were simple falsehoods about divine providence... Christian doctrine ought not to be used for that...

To interpret history as expressing God's will, God's will must accord with the most basic ideas of justice... I soon came to reject the idea of the supremacy of the divine will as also hideous and evil.

Did Rawls "fail" to justify his theory of justice? Wolff doesn't think so. Nor, apparently, do the theatrical producers behind this:

Bill Moyers has been the most philosophically-curious face on television for a long time, producing programs and companion books like

A World of Ideas, Healing and the Mind, and

Language of Life. Just watched his

late-'80s interview with Isaac Asimov, it's riveting. And Moyers' series with the late Joseph Campbell,

The Power of Myth, was a surprise smash hit. It's all about discovery and creation of meaning. "To find your own way is to follow your bliss..."

Or, as we trolley philosophers say: "Your own track, kid, and not what your guru tells you."