Today in Happiness CoPhi we consider John Kaag's fourth chapter in Sick Souls, Healthy Minds. "Consciousness and Transcendence" are big topics which I've considered before. I think Peter Ackroyd was onto something when he proposed to define transcendence in hyphenated fashion: "trans-end-dance: the ability to move beyond the end, otherwise called the dance of death." The Plato Papers

This particular dance of transcendence should not be confused with Johnnny Depp's in that film...

Consciousness is complicated.

Naturalized and pluralistic transcendence in the Jamesian vein, as I see it, takes us beyond our personal end and links us to life's great trans-generational chain, not by transmuting or "uploading" consciousness but by raising it, and introducing a wider sense of identity with John Dewey's continuous human community. "A chain is no stronger than its weakest link, and life is after all a chain," James said in Varieties of Religious Experience.

And in Pragmatism James said our really vital question is: "What is this world going to be? What is life eventually to make of itself?"

For those questions and that vision of life to vitalize ours, we must have moved beyond our mortal end. We must have come to see our own consciousness as in some important sense continuous with that of trans-temporal humanity. We move beyond our finite span of years when we begin deeply to care about the life-world beyond them.

Can we begin to do that by connecting with our own internal streams of thought? It may sound paradoxical, but that's the view James seems to defend in Principles of Psychology's Stream of Thought chapter IX. By acknowledging and embracing our unique first-person subjectivity we begin to build bridges "beyond the end," towards the other links in our vast human chain. We come to realize that, just as our own consciousness delivers the world whole and not "chopped into bits," so it is for others. The continuity and vivacity of their internal lives are as real to them as ours to us. We're in the stream together, sinking or swimming together, and though we don't know precisely what their subjective streams entail for them we know enough to recognize our shared humanity.

James lost his father and a son, in his forties. The death of precious others often propels us towards transcendence and a reckoning with death that can carry us past our grief and loss. The father's death was quite poignant, as James learned too late and from too far away that he'd not have an opportunity to say a proper good-bye in person. So he wrote a remarkable trans-Atlantic letter in December 1882.

...We have been so long accustomed to the hypothesis of your being taken away from us, especially during the past ten months, that the thought that this may be your last illness conveys no very sudden shock. You are old enough, you've given your message to the world in many ways and will not be forgotten; you are here left alone, and on the other side, let us hope and pray, dear, dear old Mother is waiting for you to join her. If you go, it will not be an in harmonious thing. Only, if you are still in possession of your normal consciousness, I should like to see you once again before we part...

As for the other side, and Mother, and our all possibly meeting, I cant say anything. More than ever at this moment do I feel that if that were true, all would be solved and justified. And it comes strangely over me in bidding you good-bye how a life is but a day and ex presses mainly but a single note. It is so much like the act of bidding an ordinary good-night. Good-night, my sacred old Father! If I don t see you again Farewell! a blessed farewell! Your WILLIAM.I read that letter to my own dad, in his terminal summer following a diagnosis of leukemia. He got the message Henry may have missed, really so very simple: a message of gratitude and love, and an assurance that his message and presence would not by his children be forgotten. Not ever.

But "the taste of the intolerable mysteriousness" of existence returned, intensified, when young Herman James passed in 1885. Is consciousness really "a mystery that human intelligence will never unravel"? It does seem likely that even a complete comprehension of how the brain gives rise to self-awareness would leave the why and the wherefore unresolved. The mystery of consciousness as a generic phenomenon is hard enough, particular consciousnesses must be harder still to crack. "The continuous flow of the mental stream" is subjective. Looking at its physical correlates does not promise deep insight.

We read also today of Thoreau and his marvelous conclusion in Walden. "Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star." As a morning person, and a saunterer in the Thoreauvian spirit, and a dreamer of human intrepidity, I find in those lines great inspiration. I'm thinking of getting them inscribed in a visible and lasting way. Ask me about that next week.

James the "nitrous oxide philosopher" would have been intrigued by Michael Pollan's (and others') advocacy of research into the therapeutic potential of appropriately-prescribed hallucinogens.

HE has short hair and a long brown beard. He is wearing a three-piece suit. One imagines him slumped over his desk, giggling helplessly. Pushed to one side is an apparatus out of a junior-high science experiment: a beaker containing some ammonium nitrate, a few inches of tubing, a cloth bag. Under one hand is a piece of paper, on which he has written, "That sounds like nonsense but it is pure on sense!" He giggles a little more. The writing trails away. He holds his forehead in both hands. He is stoned. He is William James, the American psychologist and philosopher. And for the first time he feels that he is understanding religious mysticism.Mind-altering drugs may not afford deep metaphysical insight after all, but it's becoming increasingly clear that they can help PTSD sufferers (like war vets) and others whose pain is not amenable to mainstream pharmacology. James the humanist would agree.

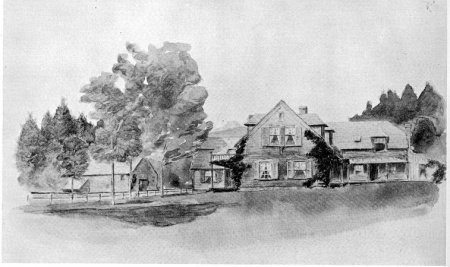

James's summer home in Chocorua, New Hampshire was a wonderful getaway for him, and an apt metaphor for his philosophy and its anchoring temperament: "fourteen doors, all opening outwards." Like a transcendent consciousness, and (though the metaphors are mixed) like a flowing stream. James loved "the open air and possibilities of nature." Fling open the doors. Get out there. Even, or especially, in November.

11.16.21

No comments:

Post a Comment