I probably come across as more generally unsympathetic to the Stoics than is truly the case. I’m not hostile, just sometimes impatient with what seems their occasional surrender to circumstance when what’s really demanded is a fight. They’d say that’s an emotional judgment, and that we need to pick our fights with the greatest deliberation. A fight with Nero wasn’t going to save Seneca’s own skin, true enough, and it wasn’t going to look good in the philosophy books alongside a lifetime of counsel against anger and futility.

But lying down and dying at the behest of a crazed despot doesn’t look so good either.

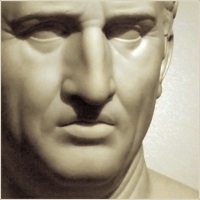

I do still think Roman philosophy gets an undeservedly bad rap. Cicero in particular is way underrated as a philosopher, and in most texts underrepresented. Jennifer Hecht rectified that a bit in her Doubt: A History.

Cicero‘s wonderful dialogue with a Skeptic, a Stoic, and an Epicurean, Nature of the Gods, would have been fun to join. “Cotta” says it all:

Are you not ashamed as a scientist, as an observer and investigator of nature, to seek your criterion of truth from minds steeped in conventional beliefs? The whole theory is ridiculous… I do not believe these gods of yours exist at all, least of all the uninvolved, uninterested ones like the Epicurean-inspired Disinterested Deist Deity. If this is all that a god is, a being untouched by care or love of human kind, then I wave him good-bye.If you want truth, as JMH observes, you have to avoid making things up.

Novelists and other artisans of the well-chosen and well-spoken word (like Hecht, a poet and historian as well as a terrific philosopher) have appreciated Cicero more than most of my philosophy colleagues. There’s Tom Wolfe‘s A Man in Full, for instance, in which Epictetus gets the star treatment.

Robert Harris’s Conspirata was good company last Fall on my daily commute up and down I-24, and before that Imperium. Simon Jones’s narration is delightful, even if he sounds a lot like Arthur Dent.

And then there’s the Victorian Trollope’s compendious Life of Cicero.

The older I get, the longer my reading list grows. Cicero said that was one of the consolations of aging. He was a wise old consul, and an honest Stoic.

After the loss of his daughter Tullia in childbirth, [Cicero] turned to Stoicism to assuage his grief. But ultimately he could not accept its terms: “It is not within our power to forget or gloss over circumstances which we believe to be evil…They tear at us, buffet us, goad us, scorch us, stifle us — and you tell us to forget about them?”But my favorite mention of Cicero in all of literature is still from Emerson:

Meek young men grow up in libraries, believing it their duty to accept the views, which Cicero, which Locke, which Bacon, have given, forgetful that Cicero, Locke, and Bacon were only young men in libraries, when they wrote those books. [An honest Stoic, 2.1.13]But they were probably not in libraries when they had their most original ideas. Our study is out in the world.

6 am/5:36, 56/87, 7:52

No comments:

Post a Comment