William James might have said our noticing problem has to do with our tendency to take flight from our various perches, giving neither flights nor perchings their attentive due. But the "transitive" parts of experience, conveying us from place to place, are especially neglected.

The flights and perchings metaphor fits Frederic Gros's analysis, according to which outside is generally regarded as a transition between insides. Transitions are obstacles, hurdles, preliminaries. Not on the long trail, though. Take a hike and the tables are turned, outside is now the stable core of life and interiors are merely conduits to more core, "milestones... to help keep you outside for longer: transitions." The "open air and possibilities of nature" (as James put it) quickly recover their ancestral status as our native element. "I live in a landscape... my home all day long..."

There's a "good slowness" that walking engenders and that our hurry-up culture disparages, a "slow-and-steady wins the race" pace (but it's not a race), a deliberation that takes its time and in the process opens time up. It exposes "the illusion of speed" as it cleaves to time and stretches it, and thus "deepens space." I'm reminded of Annie Dillard's arresting statement in For the Time Being: "While we breathe we open time like a path in the grass. We open time as a boat's stem slits the crest of the present."

And of Henry Thoreau's "time is but the stream I go a-fishing in. I drink at it; but while I drink I see the sandy bottom and detect how shallow it is... The intellect is a cleaver; it discerns and rifts its way into the secret of things." Does it, afoot? Or does it just seem that way, amidst the surge of endorphic feel-good brain chemistry catalyzed by our good and steady slowness? Either way, it's a happy feeling. When does a happy feeling announce a happy life? Well, repeatedly. Daily, for a committed walker. The days are gods, as Emerson said. "Crossing a bare common..."

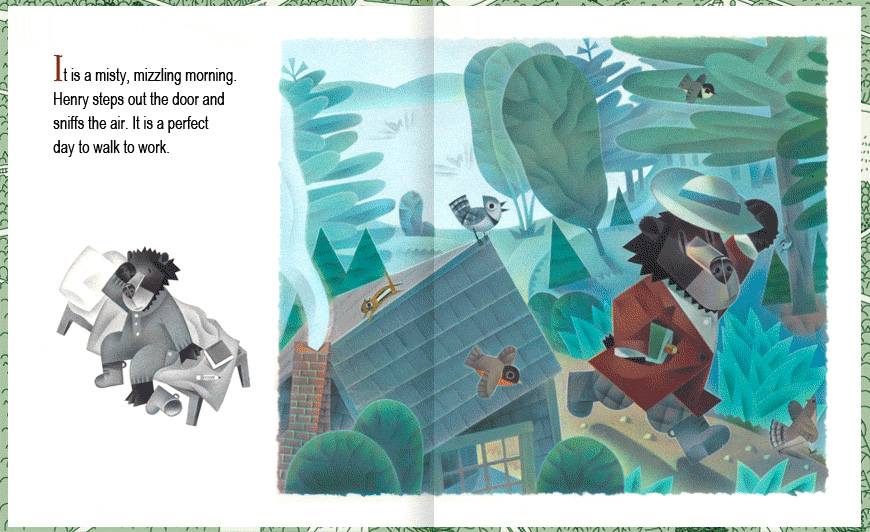

See also Henry's walk to work...

It is a misty, mizzling morning... a perfect day to walk to work.

Go Rimbaud, Patti Smith sang in an encomium to her virtual "boyfriend." And go he did, his steps generating a happy "poetry of well-being" and a self-effacing protestation that "I'm a pedestrian, nothing more." Well, a bit more: he described himself, in the afterglow of a long walk, as"blissfully happy."

Flights and perchings again. "I find in Rimbaud that sense of walking as flight," not the distracted flight of mere transition but the deeply joyous flight of departure and possibility.

Well, that's not quite right. We're doing nothing but sniffing, squirreling, circling, and (as Ms. Langer advises) noticing things. That's something, after all.***

Just ask Maira Kalman, who says dogs are "constant reminders that life reveals the best of itself when we live fully in the moment and extend our unconditional love... the most tender, uncomplicated, most generous part of our being blossoms, without any effort, when it comes to the love of a dog."

*In "On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings" William James recounts the sage advice of a "chieftain": "thou wilt never know the happiness of both thinking of nothing and doing nothing. This, next to sleep, is the most enchanting of all things. Thus we were before our birth, and thus we shall be after death."

**I think we're a good team, but research shows that humans have bred the wolfish genius for teamwork out of them - more support for Rousseau's thesis about the corruptions of civilization?

(Check out the inspiration for this Kalman

illustration, in the right sidebar: E.B. White and friend)

***Alexandra Horowitz noticed quite a lot about walking with dogs in On Looking: Eleven Walks With Expert Eyes, and before that Inside of a Dog: What Dogs Smell, See, and Know. “Dim but happy”... "A life untrammeled by knowledge of its end is an enviable life." Indeed. And a human life untrammeled by specific knowledge of the occasion of its end is relatively enviable. Ask Camus...==

It’s the birthday of writer Albert Camus (books by this author) born in Mondovi, Algeria (1913). He grew up in a working-class family. His father was killed in the Battle of the Marne, and his mother worked as a cleaning woman; she could barely read. His family lived in two rooms, and they had no money, but a grammar-school teacher prodded him toward a university education. He studied philosophy in Algiers and tended goal for the university soccer team. He wrote later, “All that I know most surely about morality and the obligations of man, I owe to football.”

In 1940, he moved to an Algerian town called Oran, where he spent time on the beach. One day, he saw a friend of his get into a fight with some Arab men and threaten them with a pistol. Soon afterward, he worked the scene into a novel called The Stranger, which became his most famous book.

It begins, “Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.” The narrator kills someone on a beach and goes to prison, where he eventually reconciles himself to his situation. He says: “For the first time, in that night alive with signs and stars, I opened myself to the gentle indifference of the world. Finding it so much like myself — so like a brother, really — I felt that I had been happy and that I was happy again.”

In the spring of 1940, Camus moved to Paris just as the war began with Nazi Germany. He got a job designing page layouts for a newspaper, and devoted most of his attention to writing The Stranger. He finished the book just before Hitler’s tanks rolled into the city. In the turmoil of that time, he wrote letters to a woman named Francine, who soon became his wife. He said, “I only know that I will maintain what I believe to be true in my own universe, and as an individual I will give in to nothing.”

The Stranger was published in 1942, followed by a collection of essays, The Myth of Sisyphus (1943). He also wrote The Plague (1947), a novel about the way people react when disease terrorizes their city. The Plague made him rich enough to quit his job at a publishing house, but he stayed. His boss convinced him to drive back to Paris one night in 1960 instead of taking the train. He was killed in an accident on the way. His unused train ticket lay in his pocket, and the manuscript of his last novel was found in the wreckage.

Albert Camus said, “[The writer] cannot put himself today in the service of those who make history; he is at the service of those who suffer it.” WA

No comments:

Post a Comment