Birthday of W.B. Yeats. His odd "metaphysical marriage" to Maud Gonne made him an even more melancholy metaphysician, to borrow a Jamesian phrase I long ago appropriated for my own purposes and regularly recall, reminding myself to lighten up about philosophy and, well, everything.

Mentioning a Yeats-like friend who was too earnestly and sensitively dependent on others for his own happiness, William James wrote in the "Sick Soul" chapter of Varieties of Religious Experience,

And so with most of us: a little cooling down of animal excitability and instinct, aJames says "the music can commence again - and again and again - at intervals," though he's much too quick in this context to attribute "the falling dead of the delight" to a naturalistic frame of mind. The problem for mild and occasional melancholics (as opposed to those who suffer deep and lasting depression) really isn't metaphysical, as he usually acknowledges, it's temperamental and habitual. And that (coupled with a robust sense of personal will) means it may be subject to personal therapeutics. We can make ourselves happier.

little loss of animal toughness, a little irritable weakness and descent of the pain-

threshold, will bring the worm at the core of all our usual springs of delight into full view, and turn us into melancholy metaphysicians.

There's an illuminating recognition of this phenomenon, or sensibility, in Darrin McMahon's discussion of David Hume. The happy skeptic's reputed dispositional cheer and bonhomie were at least partly practiced, until he taught himself the "utility of distraction" that allows a happy person to step away from distress.

Hume was at times given to melancholy and doubt, plagued by his inability to arrive at certain truth. But on such occasions, he turned, as he tells us in his first work, A Treatise of Human Nature, to a powerful antidote:

"I dine, I play a game of back-gammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends; and when after three or four hours' amusement, I wou'd return to these speculations, they appear so cold and strain'd, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther.""Common life" is the cure, not supernaturalism. I usually think of James's version of empiricism as a "radical" improvement on Hume's, but in this respect I say the Scot wins the hand.

A question to take walking: does this approach make happiness a trick, a sham, an illusion? James said "the lustre of the present hour is always borrowed from the background of possibilities it goes with"... does the happiness of common life borrow against something else? And, does my old secular reading of Yeats stand up?

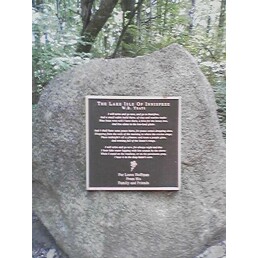

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart's core.

WB Yeats reads 'The Lake Isle of Inisfree'

![[thumbnail]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/proxy/AVvXsEi_WwZS4YuEvfV9ST6ohWrFmhYsknT5v_L66zpLWBrkWvelpf60QYo3HRmNxNIO7-EWajAbmejum6pacsA-u7lAXgwpqW-HG4umABzf4eN_pcpU2XpmO95d3XMsfZrd-SL0xumedsYRB2ZteragBcJbRTNaHw7hywtpESb-FX2BDm77epk=s0-d-e1-ft)

No comments:

Post a Comment