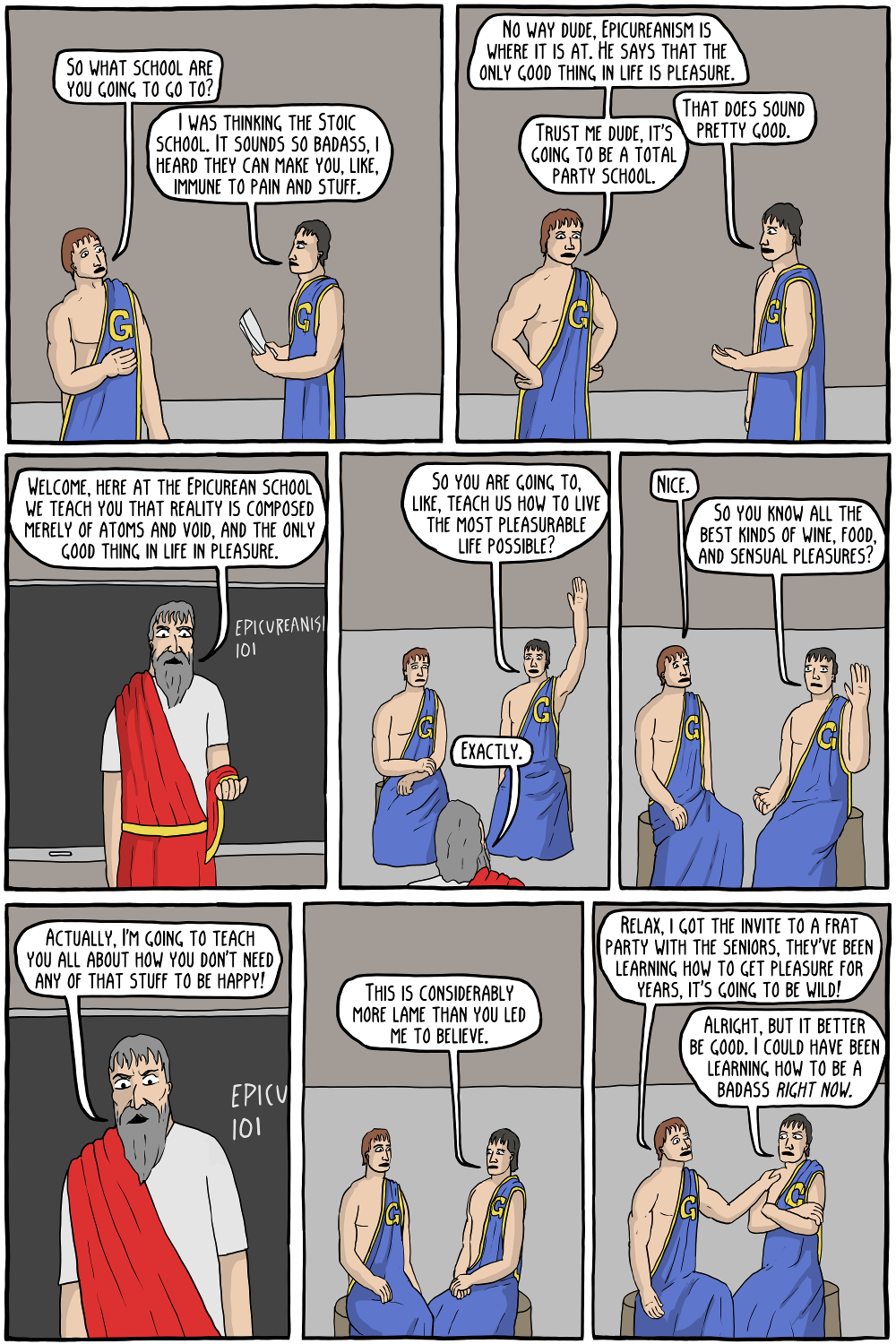

In Philosophy of Happiness we'll commence our inquiry into the ancient "Graceful-life" philosophies, especially my favorite: Epicureanism.

But we'll also consider Stoicism, Cynicism, and Skepticism.

As Jennifer Michael Hecht says in The Happiness Myth,

Ancient ideas of knowing yourself were about coming to be a better person. The process was psychological, but more in the realm of conditioning one's mind than in finding out why the mind does what it does. Marcus Aurelius said, "Cast away opinion and you are saved. Who then hinders you from casting it away?" Can we really control our emotions by decision? The best of the ancient writers, including Aurelius, acknowledged that we could not do it, and with a smile and a shrug provided exercises for teaching ourselves to improve what self-control we have. That's what religion and graceful-life philosophies are doing with their rituals and their meditations: teaching us to wake up to ourselves, for the sake of happiness. Not all philosophy overtly calls for ritual meditation. For instance, epistemology, the study of how we know things, and eschatology, the study of how things end, involve conceptual investigation. But some philosophies, throughout history, have been about how we should live. Much life advice comes as part of a particular religion or politics. To indicate a philosophy primarily concerned with advice for living, I use the term "graceful-life philosophy." The important ancient ones were Epicureanism, Stoicism, Cynicism, and Skepticism, and the term is also useful for referring to the work of the Renaissance thinker Montaigne, and of any modern thinker who offers secular, philosophical arguments for how individuals should best live their lives. . . LISTEN

My own view is that happiness is best pursued somewhere on the road between the stoics and epicureans, with an edge going to the latter. "The Stoics cared about virtuous behavior and living according to nature, while the Epicureans were all about avoiding pain and seeking natural and necessary pleasure." (Daily Stoic)

They were both right. But I think Epicureans have more fun, and are less likely to disengage from life's more pitted challenges-like the battle against mortality. Of course that's one we'll all lose in the end, but who knows when that will be? The brevity of life is no matter of indifference to me.

They were both right. But I think Epicureans have more fun, and are less likely to disengage from life's more pitted challenges-like the battle against mortality. Of course that's one we'll all lose in the end, but who knows when that will be? The brevity of life is no matter of indifference to me.

Epicureanism: the original party school

"Before he attained domestic happiness he had probably worked out his enduring philosophy of life; it was marked by cheerfulness not gloom, and he afterwards described it as Epicurean, though he hastened to say that the term was much misunderstood. He came to believe that happiness was the end of life, but, as has been said, he was engaged by the "peculiar conjunction of duty with happiness"; and his working philosophy was a sort of blend of Epicureanism and Stoicism, in which the goal of happiness was attained by self-discipline." Dumas Malone, Jefferson the VirginianAnd as for cynics and skeptics:

Most philosophers are moderate (not extreme) skeptics: their default mindset is to doubt and question what "everybody knows," so that truth, facts, and reality may emerge. George Santayana said skepticism is the chastity of the intellect, and you should guard it. But don't get stuck in doubt, like this guy (who very much resembles my dog Pita) on my desk at home. (Did you know, btw, that "cynic" means doglike?)

Most philosophers are moderate (not extreme) skeptics: their default mindset is to doubt and question what "everybody knows," so that truth, facts, and reality may emerge. George Santayana said skepticism is the chastity of the intellect, and you should guard it. But don't get stuck in doubt, like this guy (who very much resembles my dog Pita) on my desk at home. (Did you know, btw, that "cynic" means doglike?)Also, don't get stuck in epicurean hedonism, stoic resignation (Stoic Pragmatists understand this), or cynical impropriety. You'll be happy not to live in a barrel or under a cloud.

No comments:

Post a Comment